I’ve been hearing the phrase 「是在哈囉」 for a while now. The most recent case of which was a while back when a Taiwanese friend responded to a former member of the diplomatic service who wrote tell-all posts on his Facebook lodging his complaints about his former colleagues.

According to this handy slang guide from Business Next, the phrase takes its origin from when Americans say “Hello~~~?” (wavy intonation) to mean “What the f*ck is going on with you?”. Originally I’d thought the phrase meant attracting attention just for the sake of courting controversy, but according to the Business Next interpretation, it’s basically “up to f*ckery” or “behaving or acting bizarrely”.

中天 (whoops) posted this video suggesting that lots of people don’t really know what it means but get the general gist:

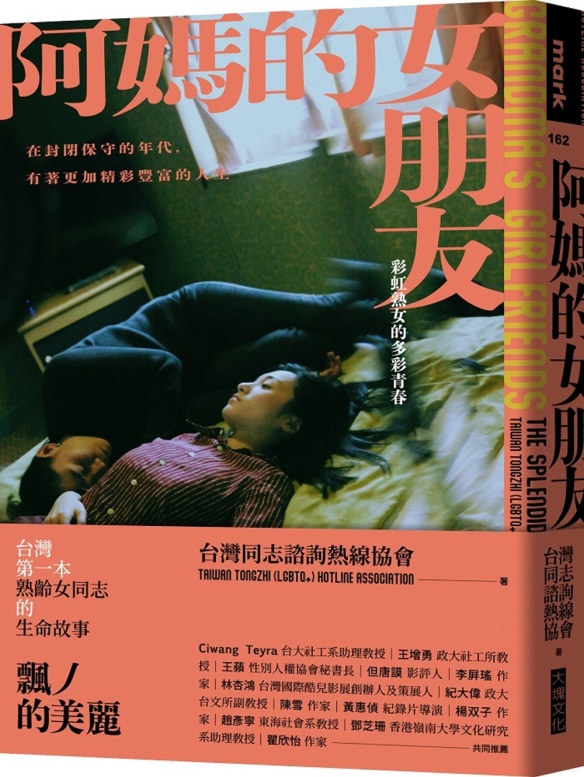

As with much slang, different people use it in different ways and it evolves over time (see the varying interpretations of 「三八」 to start your journey down the rabbit hole), so I thought I’d pick a few random examples of its use from across the internet so that you can troll strangers without nagging doubts about the appropriateness of your cutting remark on their new Instagram pics.

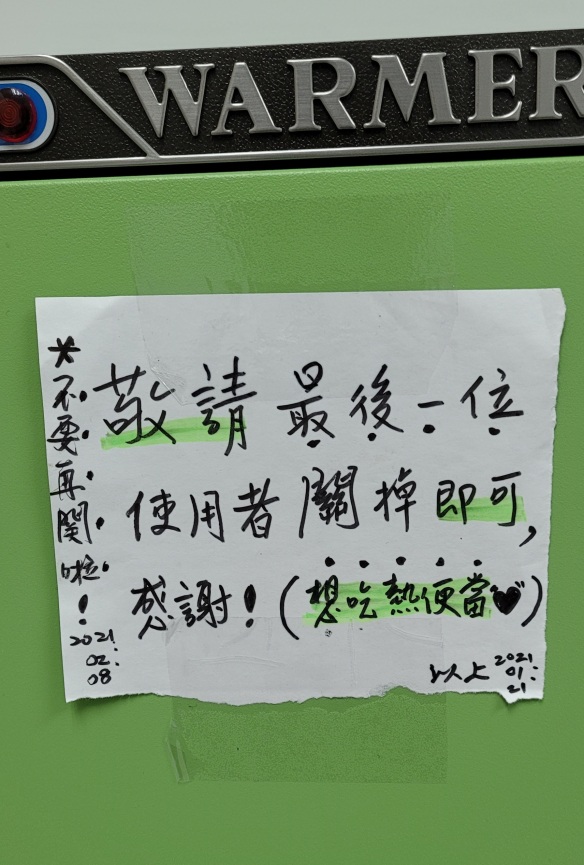

This example is an ad trying to encourage people to return to their hometowns to vote:

Even Minister of Foreign Affairs Joseph Wu has apparently employed the phrase when questioning the actions of the WHO:

A Taiwanese soap star Brent Hsu also made the Taiwanese version of the phrase popular in the Taiwanese drama Proud of You (《天之驕女》):

In the phrase 「洗嘞哈囉」, the character 「洗」 is used to represent the pronounciation of the character 「是」 sī in Taiwanese, and the character 「嘞」”lei” in Mandarin and “leh” in Taiwanese represents the Taiwanese character for 「在」 (to be doing s.t.). Then the 「哈囉」 is just a representation of the borrowing of the word Hello from English.

As you can see many of these posts are from last year or the year before, so expect saturation with this phrase at some point and a few rolled eyes if you use it at this point.

Another way to say “What the f*ck!?” in Taiwan is to use the phrase 「花若發」 (huā ruò fā) which is an approximation of the sound of the English phrase (What the f*ck) using Chinese characters (and Mandarin pronounciation).

/cloudfront-ap-northeast-1.images.arcpublishing.com/appledaily/YXJXVSMQWKFHYYZEM4BM2DFTLI.jpg?w=584&ssl=1)

/cloudfront-ap-northeast-1.images.arcpublishing.com/appledaily/AXWSCVMYMQD3OTBZM323XO26RA.jpg?w=584&ssl=1)