While ostensibly chronicling his family history, from the war-torn Vietnam his mother and schizophrenic grandmother witnessed, to the immigrant experience in the US, the author of this novel provides a breathtaking look at contemporary America, from morphine addiction to racial and class-based inequality and the politics of integration and queerness.

The novel is structured as a letter to the author’s mother, who cannot read in English, giving the author license to say things that he may never have been able to communicate with her in their common tongue, which the author describes as follows:

“The Vietnamese I own is the one you gave me, the one whose diction and syntax reach only the second-grade level. […] a time capsule, a mark of where your education ended, ashed. Ma, to speak in our mother tongue is to speak only partially in Vietnamese, but entirely in war.”

All through the book, the author plays with language in a fascinating way, at times veering into poetry, at times examining language itself, facilitated perhaps by the distance provided by his mother’s unfamiliarity with the English language:

“How often do we name something after its briefest form? Rose bush, rain, butterfly, snapping turtle, firing squad, childhood, death, mother tongue, me, you.”

For me, as well as its emotional impact, many parts of the book have a powerful wit and humour to them which made me linger over certain passages.

The immigrant experience in the US (although one could also say more generally) is captured in passages such as the one that follows, about the nail salon in which his mother works:

“In the nail salon, sorry is a tool one uses to pander until the word itself becomes currency. It no longer merely apologizes, but insists, reminds: I’m here, right here, beneath you. It is the lowering of oneself so that the client feels right, superior, and charitable. In the nail salon one’s definition of sorry is deranged into a new word entirely, one that’s charged and reused as both power and defacement at once. Being sorry pays, being sorry even, or especially, when one has no fault, is worth every self-deprecating syllable the mouth allows. Because the mouth must eat.”

The author later echoes his mother’s self-deprecation, while working on a tobacco plantation, when he meets his first lover for the first time:

“I would know only later that he was Buford’s grandson, working the farm to get away from his vodka-soaked old man. And because I am your son, I said “Sorry.” Because I am your son, my apology had become, by then, an extension of myself. It was my H

But the novel also touches on other issues in the US, like the impact of the marketing of oxycontin by the pharmaceutical industry to doctors leading to drug dependency among wide swathes of the US population and the overdose deaths of many of the author’s friends.

What I loved about the book was how real the author seemed in his thought patterns, in the realistic way memories flitted up during conversation and associations click in his mind, even if they weren’t verbalized by the character at that time. There is also an honesty to the portrayal of his sexual experiences which makes them rawer and more real. Think Peep Show‘s portrayal of sex without the comic aspect. I also liked how real his coming out conversation is with his mother, as the ball is taken completely out of his court as she confronts him with her own truths, which I think is part of a lot of people’s coming out experience.

One of the tidbits of cultural information about Vietnam was about the use of drag performers in funeral processions, which is similar but different to the gaudy performances at Taiwanese funerals:

“City coroners, underfunded, don’t always work around the clock. When someone dies in the middle of the night, they get trapped in a municipal limbo where the corpse remains inside its death. As a response, a grassroots movement was formed as a communal salve. Neighbors, having learned of a sudden death, would, in under an hour, pool money and hire a troupe of drag performers for what was called “delaying sadness” […] It’s through the drag performers’ explosive outfits and gestures, their overdrawn faces and voices, their tabooed trespass of gender, that this relief, through extravagant spectacle, is manifest. As much as they are useful, paid, and empowered as a vital service in a society where to be queer is still a sin, the drag queens are, for as long as the dead lie in the open, an othered performance. Their presumed, reliable fraudulence is what makes their presence, to the mourners, necessary. Because, grief, at its worst, is unreal. And it calls for a surreal response.”

Anyway, there’s so much more that I don’t really know how to describe, but a great read, would definitely recommend.

5/5

我最近在看一本名為《Less》的同志小說。主角Less是一位年近五十的同志小說家,他在二十幾歳的時候曾經跟一位比他大二十歳的大師級詩人在一起,但他四十幾歳的時候則是跟一位比他小二十歳的青年交往。然而,正當Less要邁入生命的後半段時,那位現在已經三十幾歳的情人找到了跟他年紀相近的伙伴,所以與Less分手。

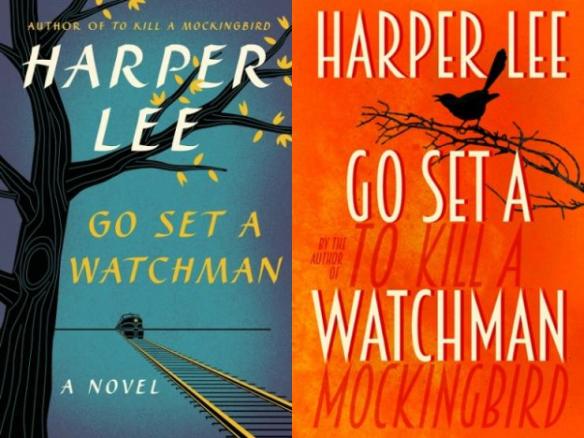

我最近在看一本名為《Less》的同志小說。主角Less是一位年近五十的同志小說家,他在二十幾歳的時候曾經跟一位比他大二十歳的大師級詩人在一起,但他四十幾歳的時候則是跟一位比他小二十歳的青年交往。然而,正當Less要邁入生命的後半段時,那位現在已經三十幾歳的情人找到了跟他年紀相近的伙伴,所以與Less分手。 (Contains spoilers) Go Set a Watchman is really a story that completes To Kill a Mockingbird and seems more relevant to the contemporary debate over race relations. The title is a quote from The Prophecy Against Babylon in Isaiah 21:

(Contains spoilers) Go Set a Watchman is really a story that completes To Kill a Mockingbird and seems more relevant to the contemporary debate over race relations. The title is a quote from The Prophecy Against Babylon in Isaiah 21: